Eight Essential Books to Learn Jazz Piano

January 23, 2021 at 6:59 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a comment

As a long-time reviewer for The Piano Magazine and a college professor for ten years, I’ve gotten to know a lot of jazz piano books – good, bad, and ugly. Here are the ones that I think are well-written, useful, and engage deeply with the jazz tradition. [full disclosure – two books on this list are my own]

- Jazz Exercises, Minuets, Etudes, and Pieces for Piano by Oscar Peterson. Buy on Amazon.

Few jazz legends ever published their own books, much less their own instructional books. Although the book doesn’t include a lot of specific guidance from Mr. Peterson in these pages, Peterson’s series of progressive pieces really do sound like the real thing. If you are open to it and a savvy learner, you’ll learn all about playing basslines, creating bebop melodies, and including swing accents. Beware – as you get towards the end of the book, the pieces get pretty virtuosic. - Playing Solo Jazz Piano by Jeremy Siskind. Buy from website / Buy on Amazon.

This book covers every aspect of playing solo jazz piano from stride to modern techniques. Even better, each chapter includes frequent musical examples as well as references to great pianists and recordings where the devices can be heard. It’s not for beginners, but for an experienced pianist who wants to be introduced to the richness of solo playing, this is clearly the place to turn. Bonus points for an introduction by Fred Hersch, one of the greatest solo pianists to ever live. - Berklee Jazz Piano by Ray Santisi. Buy on Amazon.

I always recommend this book as a recommended supplemental resource for my courses. It’s a little bit “random” in terms of what it includes – it won’t guide you progressively from one skill to the next – but what it includes is valuable, well-written and clear. There are really great hands-on tips and exercises here for basic skills likecomping, voicings, bass lines, and more advanced concepts like displacement, develop ing motives, and even writing complex counterpoint. - Dick Hyman’s Century of Jazz Piano – Transcribed! by Dick Hyman. Buy on Amazon.

It’s always struck me as odd to describe a book as “generous,” but that’s the word that comes to mind to describe Dick Hyman’s book. Hyman is one of the world’s leading experts in “stylized” jazz piano, particularly boogie woogie, stride, and virtuosic ballads. This book includes brief transcriptions from what Hyman considers essential recordings along with commentary from the author, placing the passage in historical context. There’s also an option to buy an accompanying album and DVD set. This is perfect for the jazz nerd who wants to delve into some stylistic nuances just a little bit deeper. - The Jazz Piano Book by Mark Levine. Buy on Amazon.

This one is the “classic” in the field. It covers a really wide range of jazz piano styles and techniques and has a nice list of recordings at the end. I always tell students that this is a great book to use along with a teacher. The explanations for each concept are pretty short and need a lot of practice and nuance added if you’re actually going to master the techniques. You can use it as a map for your jazz piano study, but make sure to have some guidance from a reputable source as well. - Jazz Band Pianist by Jeremy Siskind. Buy on Amazon.

Where to start with jazz piano? I usually prioritize learning about chords and voicings so that they can immediately start playing in a band. Jazz Band Pianist is a step-by-step method that guides pianists progressively from major triads to complex voicings and jazz chords. The most innovative part of the book is that pieces are presented with both “realized” version and “unrealized” versions, meaning a pianist can practice a piece with the notes written (to achieve muscle memory) and then turn the page and play the same piece with just the chord symbols (to form strong mental associations). Jazz Band Pianist is perfect for a high schooler looking to play in their school’s jazz band. - An Approach to Comping: The Essentials by Jeb Patton. Buy on Amazon.

Excellent pianist Jeb Patton did an intense deep dive into the art of accompanying with this enormous book (272 pages!) which includes two CDs of Patton demonstrating the concepts. With endorsements from important artists and lots of references to canonical recordings, this book is the real deal if you want to get into comping at a deep level. - World’s Best Piano Arrangements by Various Artists. Buy on Amazon.

Yes, this book looks and sounds cheesy, but if you’re looking for a big collection of very good jazz piano arrangements, I think it’s hard to beat. The arrangements range from intermediate to very advanced levels, but there’s something for nearly everyone here. Arrangements are by the “real-deal” pianists like “Fats” Waller, Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, Hazel Scott, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, and many more.

Perpetual Motion Etude #8

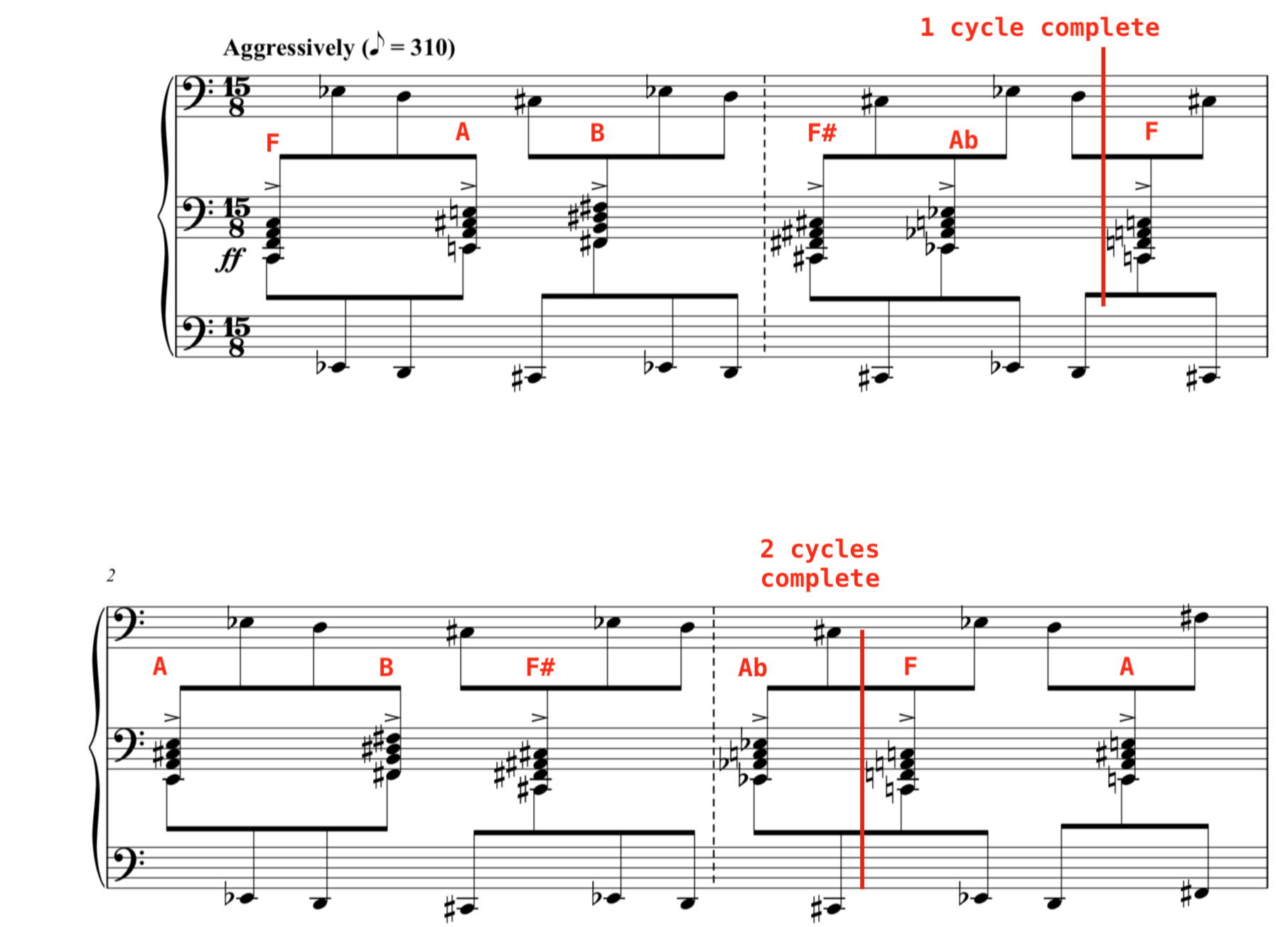

October 21, 2019 at 12:53 am | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentOf all of the pieces, Etude #8 is the most dense and had the most theoretically-based compositional process. I’m going to do my best to explain how I arrived at some of these musical outcomes.

I started with a cycle of five chords in 2ndinversion (F, E, B, F#, and Ab). I repeated this set of chords in order within a 15/8 rhythmic framework with six chords per measure. Because there is a repeated set of five chords but six chords per measure, the chords will land at different places in each measure, creating a dizzying spin.

Although the piece is titled “blues,” it’s only a blues in the loosest sense. Because the chords are merely cycling, the harmony isn’t changing in the traditional blues progression. Instead, it’s the commentary in the top and bottom staves that loosely follows the blues form – leaping up a fourth in measure 3 and returning back down in measure 4 (not unlike measures 5 and 7, respectively, of a blues form). Measures 5 and 6 are meant to imitate the cadence of a blues (normally, measures 9-10). These measures are set off from the rest because the chords change from second inversion to first inversion, making a slightly “sweeter” texture. The chromatic melody doubled in the outer staves moves down by a wholestep, just as it would in a traditional rock blues. We return to the “tonic” in measures 7-8.

The cycle of chords restarts every eight four measures. Starting at measure 9, there are only two notes for each chord because the left-hand is carrying both the chords and the chromatic melody.

Beginning at measure 17, the chords are doubled two octaves apart with “filler notes” in both hands in between.

Beginning at measure 17, the chords are doubled two octaves apart with “filler notes” in both hands in between.

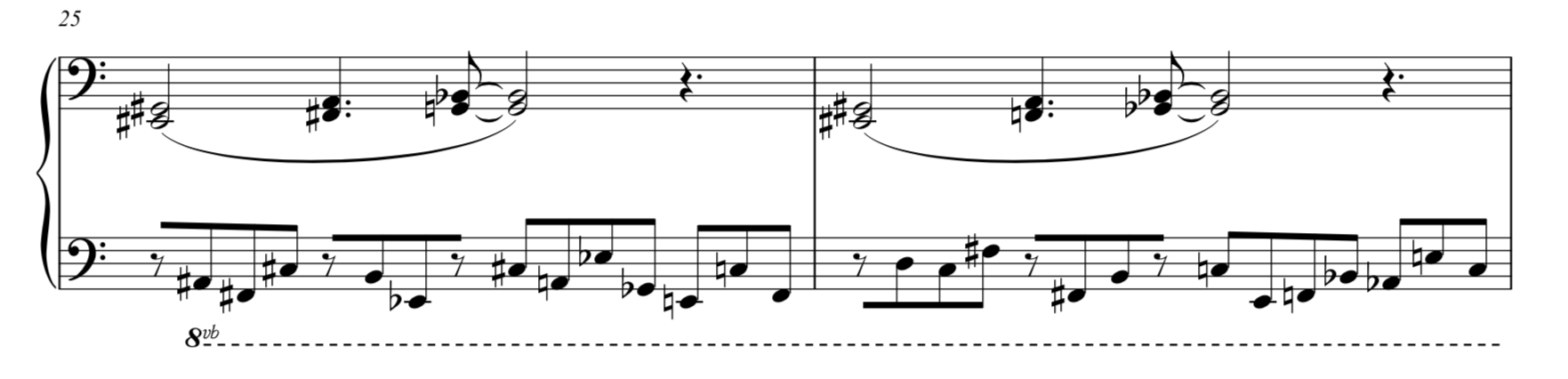

Finally, in measure 25, the chords are left out, in favor of the main “blues melody” from the top line in measure 9.

Each of these 8 measure phrases is, in my mind, equivalent to one chorus of the blues.

If you’re performing this piece, it’s all about rhythm! Give as much intensity as you can to the chords so that it feels almost like a percussion piece (one of my students compared this to “thrash rock” on the piano – a concept I totally love!). I think it’s also great to bring out the form of the blues by dropping down in dynamic during the “turn around” section (where the chords change from second to first inversion) and making a crescendo each time. This helps the listener not get completely lost in the “shifting sands” of the cyclical chords.

Here’s a clip of me giving some performing tips for Etude #8, “Blues”:

Consider a Donation

I hope you’ll consider donating to my Kickstarter and pre-ordering the CD and book of my Perpetual Motion Etudes. Click here to visit the Kickstarter page.

Integrating Improv

August 2, 2019 at 12:51 am | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentI hope that both classical pianists and jazz pianists will play my Perpetual Motion Etudes!

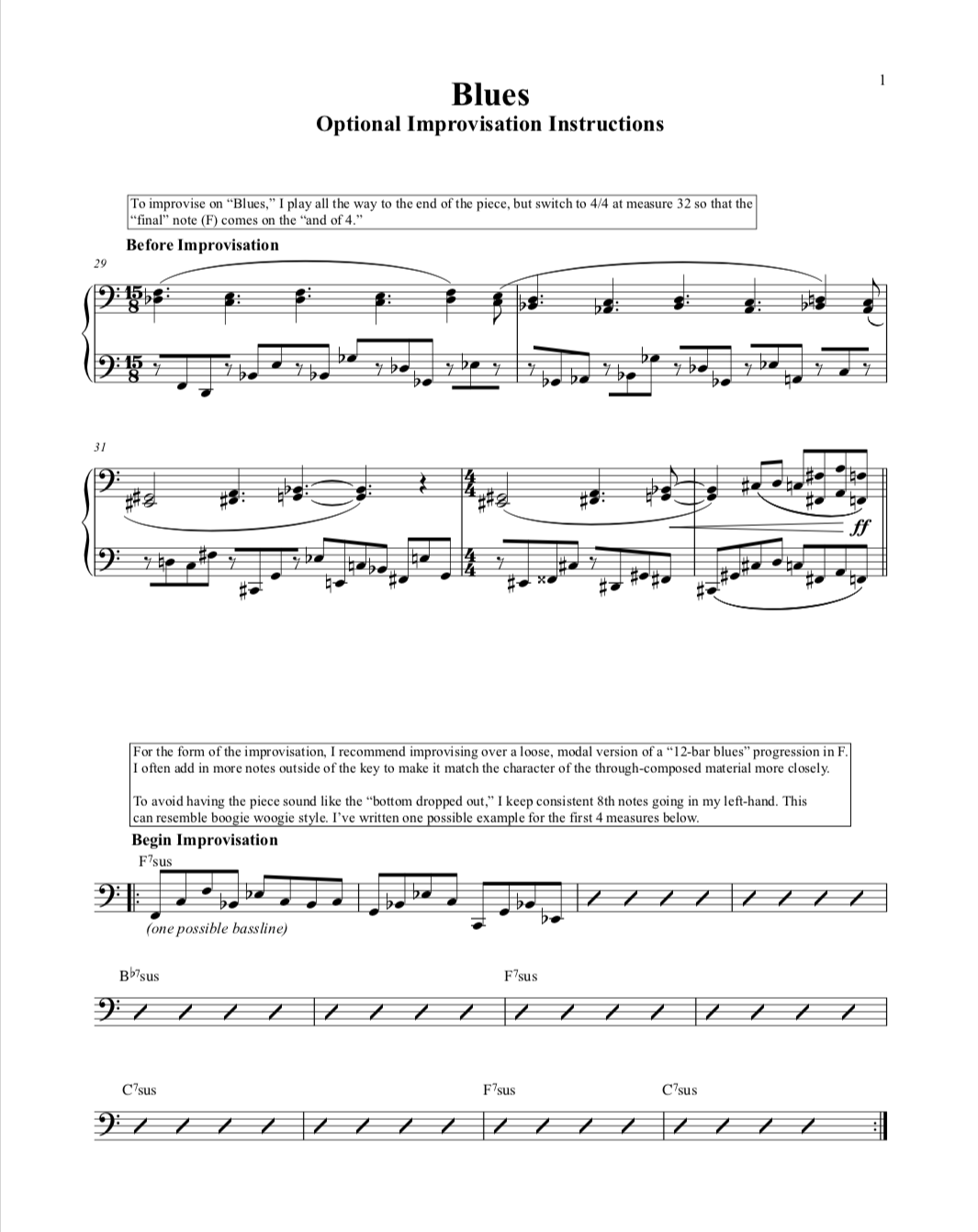

I designed these pieces so that they can be played as through-composed miniatures without any improvising. However, I can’t resist adding my own improvisation, and adding improv sections can be each piece feel like a more complete musical journey. The book version of the etudes includes “Improvisation Instructions” with improv suggestions for each piece.

The biggest challenge for improvising on these etudes is that the textures are so dense that “normal” jazz improvising (right-hand melody, left-hand bass or chords) mainly doesn’t musically connect with the written-out etudes. Trying to improvise in traditional jazz styles after playing these etudes can leave the listener feel like the bottom’s dropping out of the music.

I had to do a lot of discovery in order to figure out an appropriate platform for improvisation for each piece. I’m going to show a couple of the improvisation sections here:

Etude #2: Van Gogh’s Dream

I have to thank the great pianist-composer Vardan Ovsepian for helping me with this. I was struggling to find a way to maintain the density of this piece and improvise, and Vardan suggested putting the entire perpetual texture into the left hand, leaving my right-hand free to make some melodies. I came up with a short chord progression and did a lot of coordination practice to be able to improvise while making new melodies. You’ll also hear what I think of as a “hand-over-hand” texture where there’s no accompaniment, but only arpeggio-like exchanges between the right and left hand.

Etude #5: Piccadilly Circus

This piece has the most traditionally “jazz” improvisation. It’s the only piece where I fully stop and start between the “head” and the “solos.” I decided I wanted one opportunity to play some swing music and this piece has a traditional “jazz standard” progression that lends itself well to swing. I also felt that the tempo of the piece felt a little bit slow for the solo – because the texture of the piece is so dense, I think it feels faster than it actually is and the solo felt slow. Therefore, as the written material ends, the pianist enters with a different tempo and a swing feel.

[to preorder the etudes, click here]

Etude #8: Blues

You can read all about etude #8 here. Although the body of the piece is only loosely related to a blues, I thought it would be fun to make the solos an actual blues. You can follow the blues form if you listen closely, however, because of the atonal harmony of the written-out portion, I felt obligated to obscure the blues form with lots of chromatic notes. I ultimately used a lot of triads as part of the solo to relate back to the triads that cycle through the written-out material.

Etude #9: Enchanted Forest

I modelled some of the harmony off of Oliver Messiaen as a kind of post-Debussy haze. Since the piece is rubato all the way through, I decided that free improvisation is the way to go. Here, the pianist is authorized to do anything that they like with only one instruction – they must transition from Bb major to G major by the end of the improvisation. Of course, the pianist’s improvisation should somewhat stylistically match the other sections – a Mozartean improvisation or Bill Evans-y jazz improvisation probably would be too dissimilar to the rest of the piece to satisfy a listener.

[to order the sheet music for “Enchanted Forest,” click here]

Consider a Donation

I hope you’ll consider donating to my Kickstarter and pre-ordering the CD and book of my Perpetual Motion Etudes.

A New Way to Record

July 26, 2019 at 11:28 am | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWanna bet I can’t play my 7th etude (called “Floating”) without touching the keys?

Don’t believe me? Watch the whole video:

Am I master magician? Nope, Yamaha has invented a genius and terrifying new way to record a solo piano album using Disklavier technology. Read on to find out!

If you’re not familiar with the Disklavier, it’s a 21st century, digital version of the player piano. It’s fully capable of playing back anything you play with 1024 levels of key and hammer velocity and 256 increments of pedal position. It’s also capable of recreating performances live across the country or across continents, a feature that’s mostly used for long-distance teaching, but has also been used for a splashy Yamaha event where Elton John played a “live” performance on Disklaviers in 11 countries throughout the world.

Yamaha has decided to offer their artists use of this instrument for recording purposes for a pretty revolutionary recording experience. Here’s how it works:

- You perform your pieces on the instrument. Right now, the best place to do this is at the magical Yamaha Artist Salon on 5thAvenue in New York, overlooking high fashion shops and a bustling city street. They’re recorded not as audio, but as MIDI data. This means there aren’t any microphones, but instead, the piano is saving files with information about pitch, timing velocity, length, and pedal.

- You get to edit the data. Amazingly, you can actually take this MIDI data home and play around with it. You can pretty much change the data in any way you want, although I was advised not to edit too highly or the music might ultimately sound “artificial.”

- You play the edited tracks back through the piano, now fully mic’d to create an audio recording. Voila! You’ve got a CD!

The Good

- You can fix mistakes! There are so many things that can go wrong in a regular recording session. A single wrong note might make a take unusable or you might spend hours attempting to edit out a misplayed chord. Now, changing virtually anything about the performance is as easy as dragging and dropping. The engineer, Aaron, advised me, “Just get the poetry of the music right. Everything else we can fix.”

- Outside noise isn’t a problem. I had videographers running around while I was performing. Deliverymen entered the studio while I was mid-take. Usually, we would have had to stop the session because the microphones would pick up all the disruptions….but since the piano wasn’t actually recording audio, we were able to continue recording without concern.

- Editing is wonderful! It’s powerful! It’s educational! I learned so much about my piano playing by going into editing detail. I was able to clean up mistakes, catch places where my score differed from my performances, and even fill in some improvisations that sounded empty. I almost felt guilty adding, changing, and cutting so liberally, but I kept reminding myself that the goal is to make the best-sounding, most-enjoyable music for my audience.

Look at the editing view for a part of my Etude #2 “Van Gogh’s Dream” at two different levels of detail, You can see that you can edit the position, pitch, length, and velocity of each note.

The Bad

- The piano has to be exactly the same. I recorded the MIDI data in March but didn’t record the audio until June. In that time, even with world-class maintenance from the Yamaha team, a piano will change. For example, the pedal height had changed in the meantime, so we had to spend quite a long time trying to find the pedal height that would most accurately replicate my original performance. I think we did pretty well, but there were a couple tracks on which I wonder if the pedaling is really, exactly…mine.

- Over-editing happens. Once you canbe perfect, if you’re an obsessive perfectionist like me, it’s hard to not try to be perfect. I didn’t get totally psycho with the editing – I think it very much still sounds like me playing the music – but I would understand arguments that I over-edited some places for cleanliness. Maybe some character was traded for cleanliness, maybe not. It’s hard to say for sure.

- You lose some atmosphere. I’m a pianist who unconsciously vocalizes with my playing. Although I’m by no means a “good singer,” I kind of like hearing some of my favorite instrumentalists sing, groan, or moan along with the music (I’m looking at you, Keith Jarrett and Kurt Rosenwinkel). I wouldn’t want vocalization to be distracting, but I sometimes enjoy hearing how emotionally invested a musician is. With this Disklavier recording process, that element is lost entirely.

The Ugly

Lastly, using this process, you can create technically unplayable piano pieces, á la Conlon Nancarrow. I decided my 8thetude could use a visceral, impactful treatment, so I made this version, where there is often the equivalent of 3 pianists performing over 6-8 octaves:

Overall, I had a totally fantastic experience recording for Disklavier. For a solo piano recording, the advantages can’t be beat and the “extracurricular” possibilities are still mostly untapped.

Consider a Donation

I hope you’ll consider donating to my Kickstarter and pre-ordering the CD and book of my Perpetual Motion Etudes.

Why Perpetual Motion?

July 19, 2019 at 11:00 am | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentPerpetual motion is a pianistic texture in which, between their left and right hands, the pianist plays every single beat without stopping. You could describe the back-and-forth between the hands as fitting together like the gears of a clock, interlocking like the blocks in a well-played game of Tetris, or trading off like a game of tennis.

[to visit Jeremy’s Kickstarter page, click here]

Mehldau & Hersch

So, why perpetual motion? My interest was piqued by recordings by two of my favorite pianists.

When I was in college, I became a bit obsessed with Brad Mehldau’s piece, “Resignation.” I transcribed and performed the whole thing and was amazed by his ability to create this unrelenting sonic entity that grooved in the way I usually associate with larger groups. He was also able to create such variety even in this constant-eighth note texture with accents and hand-over-hand choreography that felt like a magic trick. Surely, this wasn’t possible on the piano!

The second recording was of Fred Hersch and Nancy King performing “Day by Day.” There’s this moment in the piano solo where Fred is going on like normal, and then he suddenly switches to this single note repeated texture which blossoms, leaf-by-leaf into this incredible pointillistic improvisation, with Fred never missing a beat. I wanted to be able to do this!

[to go straight to the Kickstarter page, click here]

Moving towards “Flow”

I wrote my first Perpetual Motion Etude in Paris. I’d done something nice for myself and extended a teaching trip by booking an Airbnb with a piano in Paris for 6 nights to do some composing. I wrote the piece “Sometimes I Wander” as an etude for myself to start to explore some of these perpetual textures.

As I practiced the piece, I realized that it was training an area where I desperately needed to grow. You know that feeling when you are talking to someone and all of a sudden your brain just can’t locate the word you’re searching for? That happens to me all the time in conversation.

Has it ever occurred to you that that can happen to musicians too?

One of my constant struggles at the piano is that I’m often plagued by distracting outside thoughts when I should be present at the instrument. These thoughts manifest physically in many frustrating ways – losing focus, tightening up, or breaking my sense of flow. To be painfully honest, ego-driven thoughts are the most frequent culprit (“You should be showing off your technique,” “audiences really expect more groove in a jazz set,” “why don’t you play more in the style of [person x]?”). These thoughts send me tumbling downwards into the mediocrity of bad decision-making and imperfect performances.

The science of “flow” or “peak performance” is actually fascinating. Neuroscientist Arne Dietrich describes the state as an “efficiency exchange” between conscious and subconscious systems. In other words, the fluid artist gets into a semi-subconscious state when performing, with parts of the brain that would shut down quick decision making shut down. Self-monitoring and hesitation go out the window. In fact, Dr. Charles Limb has done work specifically tracking the brains of improvising musicians. Check out his TED talk:

I took the “flow profile quiz” at the Flow Genome Project (try it and let me know what you get!) and I was classified as a “Deep Thinker.” Some of the insights seemed right on (“You crave time to return to your sanctuary for rejuvenation” and “Your particular sensitivity to a modern “always on” society might make you deeply out of place.”).

As I learned more about flow, I realized that I needed to consciously work on controlling these outside thoughts and “negative self-talk.” It occurred to me that perpetual motion is a texture that “forces the issue” of flow. These pieces can’t create a flow state, but – since there’s no stopping between the hands – they serve beautifully as a conscious training for getting and remaining in my most high-performing state because anything less will result in musical disaster! In other words, these pieces raise the stakes on winning the “mental game” of music.

I made a funny video talking about the problem I think the perpetual motion etudes are solving. Check it out below:

Consider a Donation

I hope you’ll consider donating to my Kickstarter to pre-order the CD and book of my Perpetual Motion Etudes.

Click here to visit the Kickstarter page.

at_Home/at_Play 7: Bye Bye Blackbird

February 28, 2018 at 6:42 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWatch Bye Bye Blackbird (at_Home)

Watch Bye Bye Blackbird (at_Play)

I think comparing these two videos is the best way to understand why I love working with this group so much. We’re able to play the song wildly differently depending on the setting, but I think both performances are effective and powerful.

For me, “Bye Bye Blackbird” is Nancy Harms’ signature tune. It captures her so well – it’s dark and exotic, it’s classic yet surprising, and it tells a story about leaving comfort to seek higher ground.

Nancy always introduces her arrangement by saying that this tune is usually done as a straight-ahead swinger, but she decided to go a different direction with it, because whenever she delivered the lyrics of “Bye Bye Blackbird,” she noticed a depth in them. The song is about leaving what’s familiar in order to take a chance, something that – for those who know Nancy – resonates with Nancy’s own story. Nancy was a small-town music educator before she decided to seek big cities, a singing career, Europe, and adventure through music. Nancy says – and I think rightly so – that leaving one’s comfort zone often seems obvious to other people (“of course he should get out of her bad relationship,” or “obviously, you should quit that job with bad hours”) but even small changes require great bravery for those willing to try something new.

Musically, this arrangement from Nancy and Robert Bell uses a bass ostinato to resituate the tune in a minor key. For our arrangement, we had Lucas play the bass part on the bass clarinet, whose dark, deep moodiness matches the mystery of the tune well, I think. Then, the bridge is an arrival point in major, a kind of “pay off” in the middle of the story. The whole arrangement is a giant swell and the ebb, starting with just the exposed texture of bass clarinet and voice and adding elements, volume, and complexity before receding back to the original duet.

In comparing the two performances, I took a very different approach on the piano. Whereas the Blue Whale performance is more percussive and groovy, with more “flashy” piano playing, the house concert performance is all about mood. My favorite moment in the Blue Whale performance is at 4:44 when Lucas and I organically switch places – he takes the lead and I play chords under him; I love that we can have the kind of unspoken musical relationship that we’re both able to step to the front or the back when the music calls for it. The house concert performance, in contrast, has a clear Debussy/Gil Evans influence and really sounds clearly modal in a way that the other doesn’t.

I’m posting a poll over on my Facebook page about which performance people like better. Feel free to click this link to visit my page and take the poll.

Download the free “at_Home/at_Play” EP here.

Bye Bye Blackbird

Pack up all my care and woes

Feeling low here I go

Bye, bye blackbird

Sugar’s sweet so is he

Bye, bye blackbird

And all the hard luck stories they all hand me

I’ll arrive late tonight

Bye, bye blackbird

at_Play 6: Hymn of Thanks

February 21, 2018 at 7:29 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWatch “Hymn of Thanks”

“Hymn of Thanks” was the result of my study of Bach Chorales. One of my best experiences in college was doing an “independent study” course with Dariusz Terefenko that was focused on improvising fugues and other Bach-ian styles. As part of the study, he showed me a book which had all of the ways that Bach harmonized and reharmonized the same chorale melodies. This fascinated me and I memorized quite a few of the harmonizations.

Then I asked myself – why couldn’t I harmonize these melodies in a way totally differently than Bach would? So I started writing “jazz” harmonizations of some of these hymn melodies. The melodies are so singable and diatonic that it occurred to me that one could do almost whatever they wanted underneath and it would still sound like a coherent musical idea. One inspiration for these reharmonization was Don Byron’s “Himn.” Listen here.

It wasn’t a far step from these exercises to writing my own hymn-like melody to harmonize. Once I wrote a simple 8-measure melody, and came up with a harmonization, I decided that this technique could result in an AABA tune, and so I made a bridge in Ab (the original melody is in C) to complement the original.

I originally recorded this piece on Simple Songs (for When the World Seems Strange) as a duet with Jo Lawry, and I must credit her with helping me come up with the form (as well as polishing some lyrics! Thanks, Jo!). She realized that this was a story song and that going through the whole story once, playing a solo, and then going through the story again was too much and we’d have given the ending away! Instead, we play AAB, then do the solos, then do the bridge again and the final A. In this way, we save the ending for the very last time through.

It was my idea to make a solo section where the chords – which generally move at one per beat in a hymn – move twice as slowly in order to give the improviser a better chance at hitting them. I can’t speak for Lucas, but for me, one inspiration for the feel of the solo was the Hank Jones/Joe Lovano record “Kids.” I love the way that Hank can play stride without it seeming cheesy or old-fashioned and how Joe can dance around the changes without ever sounding like he’s playing “out.” Check out a great live performance here.

To download sheet music for “Hymn of Thanks,” click here.

To download the free “at_Home/at_Play” EP, click here.

Hymn of Thanks

Wise men recommend a prayer

Though you may be filled with angst.

Still, for the memories we love best

Let all the bless’d sing a hymn of thanks.

I’ve been told to treasure wealth

In my friends and not in banks,

We had a flowing treasure chest,

Let all the bless’d sing a hymn of thanks.

I’m thankful for the sun and shade,

The moon that lifts the sagging tides.

I’m thankful for summer love we made,

Before you left my side.

But you are gone and I abide

Solemnly resisting ranks

Of solemn choirs who suggest

That all the bless’d sing a hymn of thanks.

at_Play 5: Kneel

February 14, 2018 at 5:05 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWatch the Video for “Kneel”

Scroll to the end to download sheet music, read the lyrics, and download a free EP, including “Kneel.”

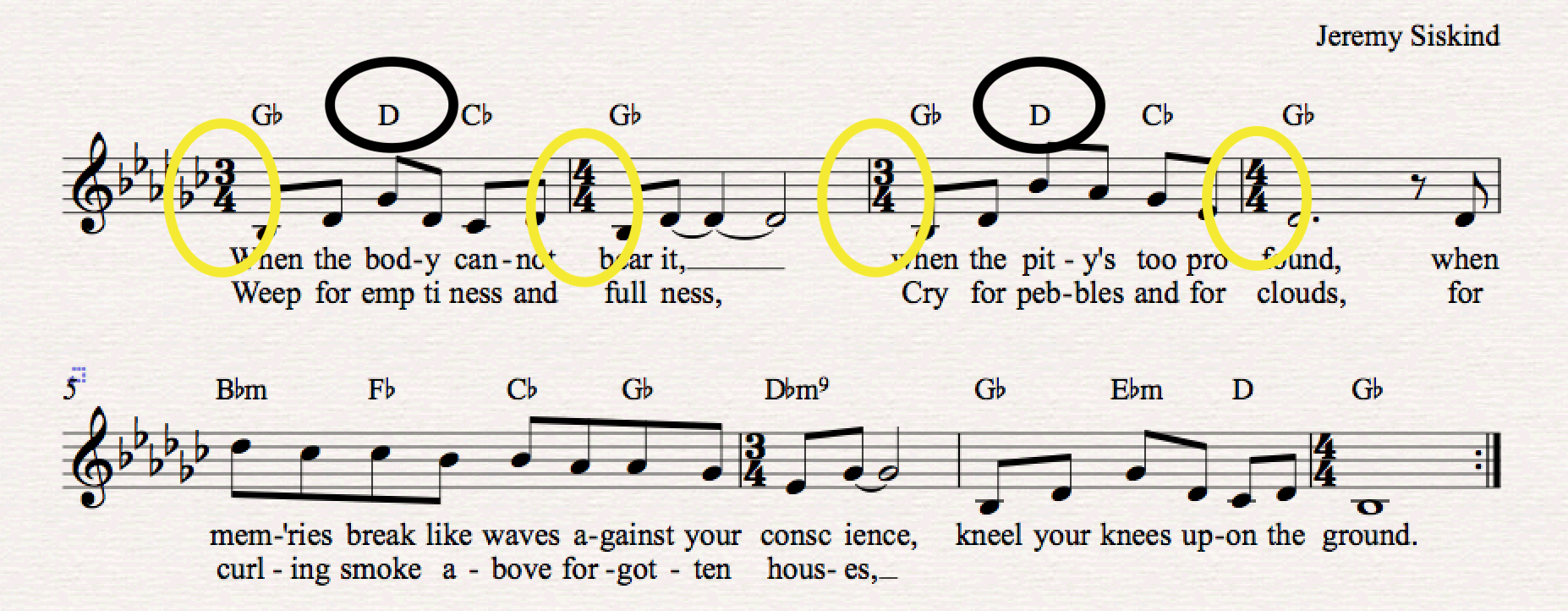

“Kneel” is a song inspired by Caribbean poet Derek Walcott’s autobiography, Another Life. In one passage, Walcott describes having a pseudo-religious experience – he takes in the colorful richness of his island of St. Lucia and is moved by its beauty, but in the same glance, he sees the suffering of the St. Lucian people and is moved by the injustice they face. Processing these polar opposites together in one place, this moment brings him to his knees in revelation – or at least, in overwhelming depth of feeling.

The power of the passage and the language that Walcott uses was moving to me, and I tried to turn it into a melody. The melody I came up with is hymn-like and simple, but I harmonized it with chords that don’t quite fit the theme – notice that the D major chord is far outside of the home key of Gb. In fact, I later realized that I’d used a similar progression for my song, “A Single Moment” – listen here.

Another complexity that undergirds the A sections of “Kneel” is the phrasing. Each of the first two phrases of the melody are in 3/4 time but the third phrase stretches to 4/4. That small difference, perhaps, keeps the melody from being too saccharine and predictable. One model I had here was Fred Hersch’s “Valentine,” which seems so sweet and simple, but actually moves freely through metric variation (listen here).

The bridge is a contrast, much more harmonically rich and with longer phrases; it’s meant to be lush and beautiful. The rhythm is repetitive, but the chords change color and melody changes shape each time the rhythm returns. I later realized that some elements are similar to the phrasing of Gerald Clayton’s “When an Angel Sheds a Feather,” a song I really admire. This link will bring you directly to the part I’m talking about.

The lyric I’m most proud of in this piece is, “Hear the bugle-colored twilight blowing.” The line feels, to me, like an Escher drawing – it’s got a logic that seems like it could be followed, but each path you follow only leads to more confusion. Twilight can’t blow and just because it’s bugle-colored, that doesn’t mean it will do what a bugle does! However, there’s a certain sparkle, a certain sheen, and a certain regal-ness that all come through in that line, and I’ve always been proud of it.

In terms of form, this piece is a bit odd, as it’s a very traditional song, yet the solo section is a free improvisation, rather than a reading through the form. Interestingly, audiences seem to really enjoy this – particularly if I introduce the thematic tension at the heart of the piece (beauty v. suffering), audiences seem wholly able to accept some pretty dissonant improvisations and allow their imaginations to fill in the content. Perhaps the prettiness of the “head” contrasted with the “ugliness” of an improvisation makes both sides more stark, more interesting.

Whatever the reason, this seems to be audience’s favorite piece, despite (or because of) the avant garde elements. This recording at the Blue Whale is a little funny, as this piece seems almost too intimate for a jazz club – it’s perhaps more in tune with the house concert audience. Here, Lucas and I take chances feeling one another out and – just as our roiling improvisation wants to come to a close – we’re interrupted by a crashing sound of some sort, and Lucas decides to react with a clarinet squeak. This sends us in a whole other direction! Just as the improvisation comedian is trained to say “yes and,” as improvising musicians, we want to accept anything that comes at us. So, kudos to Lucas for such a quick-thinking reaction!

Lastly, I was really honored that Kendra Shank and Geoff Keezer recorded a version of this piece during their live album. Geoff plays amazingly on the recording and Kendra’s vocals are warm and expressive. You can actually watch their live recording here. It could be an interesting comparison!

To download the sheet music to “Kneel,” click here.

To download a free EP with music from “at_Home/at_Play,” click here.

Kneel

When the body cannot bear it,

When the pity’s too profound,

When mem’ries break like waves against your conscience,

Kneel your knees upon the ground.

Weep for emptiness and fullness,

Cry for pebbles and for clouds,

For curling smoke above forgotten houses,

Kneel your knees upon the ground.

A schoolgirl in blue and white,

Whirling in evening’s light,

A kiss by the boathouse door

Leaving you needing more,

The horns of the harbor heard

Chanting love, word by word,

To live it is raw and rare,

Like a prayer, everywhere…

Feel the soil soft beneath you,

See the hills in ochre drowned,

And hear the bugle colored twilight blowing,

Kneel your knees upon the ground.

at_Home 5: What is This Feeling

February 10, 2018 at 7:28 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWatch “What is That Feeling”

Scroll down for free downloads and complete lyrics.

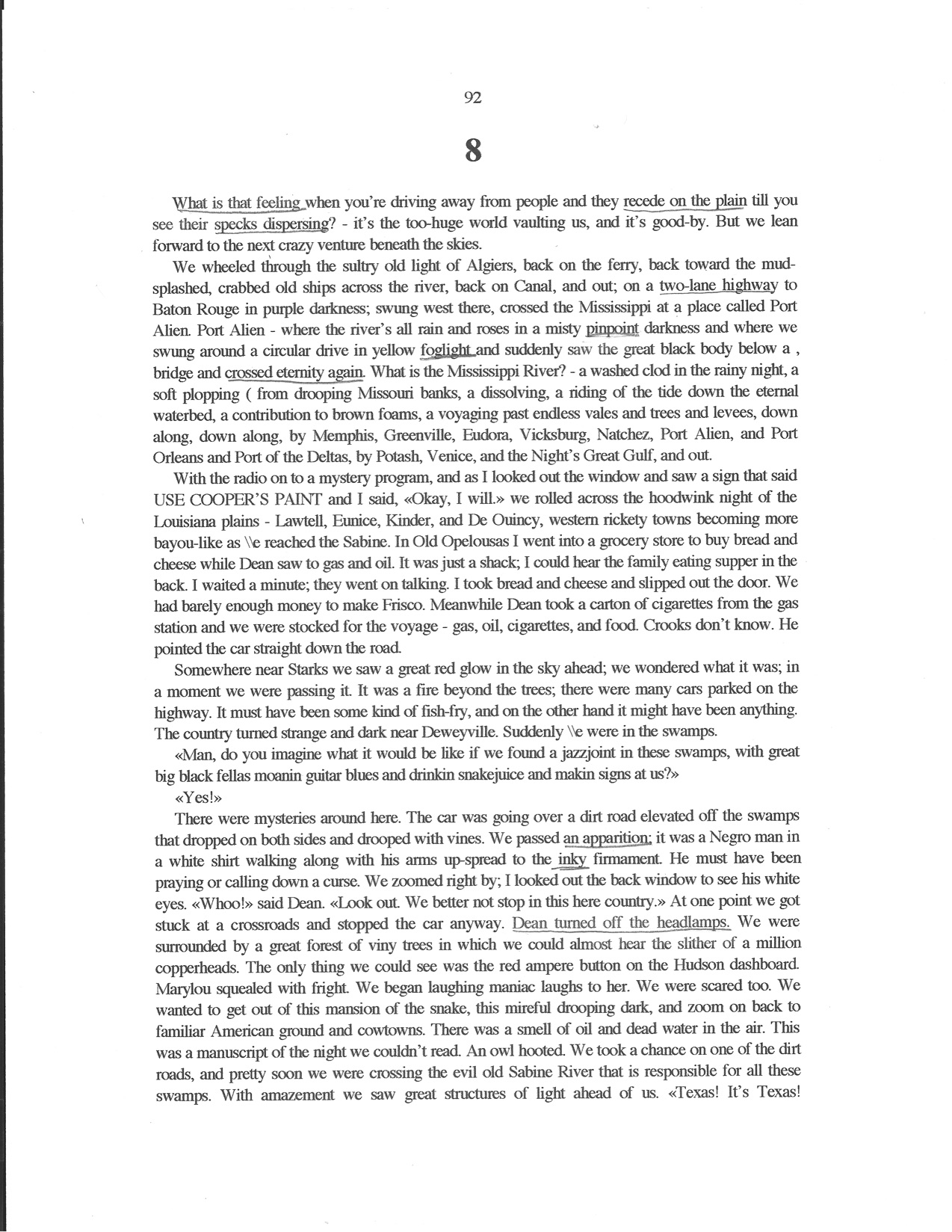

“What is that Feeling” takes its title from a passage by Jack Kerouac in On the Road. On the Road is one of those books that it seems every teenager or college student has a passionate infatuation with, and I was determined to be “cooler than” liking it myself, but – gosh darn it – that Kerouac fellow can write. It was this passage in the middle that really got me:

“What is that feeling when you’re driving away from people and they recede on the plain till you see their specks dispersing? – it’s the too-huge world vaulting us, and it’s good-bye. But we lean forward to the next crazy venture beneath the skies.”

There so much interesting here – firstly, I love that Kerouac recognizes that there’s a feeling that he can’t name – something too big or confusing or complex for a single word or term to capture it. I love that he asks, “What is that feeling…” instead of attempting to name it.

Secondly, there’s this amazing way he has of zooming in and out, and here he does it to exaggerated degrees – first the “specks dispersing,” then the “too-huge world” and “beneath the skies.” We’ve gone from microscopic level and all the way to planetary levels in a matter of a few sentences.

Lastly, I loved how he captured the mindset of a traveler, and how beautifully it relates to the psychology of a touring musician. As a touring musician, on each stop, you meet special people, and perhaps visit special places. Just today, in fact, I was in Skagen, Denmark, and visited the country’s northernmost point, where two currents violently collide above Jutland. A generous man named Larss took us to admire this point, which was an important strategic location during World War II, as it is necessary to control trade to the Baltic states. Yet, even as you settle into a memorable spot, you also maintain the excitement to visit the next, place, meet the next group of people, and see something else special. There’s a frantic energy that encompasses this flurry of “hellos” and “goodbyes” that Kerouac captures so well here – a somehow hopeful nostalgia.

Lyrically, I stole a lot from the passage where Kerouac contemplates these mysteries, and the next, in Kerouac, in which Dean and the boys drive through a somewhat haunted terrain. Below, you can see the passage with all the text underlined that I stole from. I tried to find language that fit the song rhythmically and that seemed suggestive in terms of an image.

Musically, the piece is a highly altered blues. The form is still twelve measures, and most of the arrival points remain the same (for example, we still start on the I chord and make it to the IV chord in measure 5), but there are a lot of additional colors in between, and the chords change every two beats. It wasn’t intentional, but the sounds and the approach maybe slightly resemble the work of Charles Mingus. Goodbye Pork Pie Hat comes to mind as at least a conceptually similar tune. The one time the harmony slows is when the “refrain” comes in (“Switching off the headlights”).

Lyrically, there are three verses – we do the first and second at the beginning, then Lucas plays a solo, then the second (again) and third at the end. The longer we’ve played this tune, the more that we’ve emphasized the spaciousness in the last verse, which has my favorite lyric (“the stars are pins”), which I like to play in the top end of the piano for a word painting effect. This third verse is the moment where things zoom in – they go from very general to very specific, mostly because a mysterious “her” is finally introduced into the song, which clarifies the scenario as – likely – one of romantic loss.

I suppose all of life is a bit like being the touring musician. In order to achieve another level or pursue another ambition, you have to leave something else behind. Therefore, in some way, each step in a journey is simultaneously a hello and a goodbye.

Download the sheet music for “What is that Feeling” here.

Download the free “at_Home/at_Play” EP here.

What is that Feeling?

An apparition, to curse and praise,

the face receding on the plain;

The specks dispersing, the inky skies,

what is that feeling you feel?

Switching off the headlights, you park the car and start to cry,

What is that feeling you feel?

The yellow foglight, the rainy bridge,

you cross eternity again;

The two-lane highway is endless night,

the center line is a dream;

Switching off the headlights, you park the car and start to cry,

What is that feeling you feel?

You knew you’d leave her, but who knew when,

tonight you’re driving through the fog;

The sky gets bigger, the stars are pins,

and in that instant, it’s real;

Switching off the headlights, you park the car and start to cry,

What is that feeling you feel?

at_Play 4: One Art

February 6, 2018 at 9:20 pm | Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a commentWatch the Video for “One Art”

Scroll to the bottom for free sheet music, link to a free EP, and full song lyrics.

The genesis of the song “One Art” comes from reading Elizabeth Bishop’s beautiful poem of the same name. I’ve read it in a few different classes, but I remember it most recently from a poetry seminar I took at Columbia with Michael Golston. The poem stands out to me in modern poetry because it’s so easily understood, so cheeky, so humorous, so unassuming and colloquial in contrast to the density of your Eliots and Pounds; yet, it wields equal depth and power as any works of those masters. Here’s the poem in full:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

To be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! My last, or

Next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

– Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

The art of losing’s not too hard to master

Though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

(Elizabeth Bishop)

(Elizabeth Bishop)

I remember that as I read the poem at Columbia it felt almost impossibly sad. The nostalgia was overwhelming. The essence of nostalgia, I thought as I read the poem, is the recognition that return is impossible. That is, as much as you may long to re-experience an innocent time or to rekindle a lost romance or to see a deceased friend once more – it’s an impossibility from which there is no return. This poem begs us to teach ourselves the acceptance of this impossibility but it also rails against the unfairness of such a world that tortures us with such loss but doesn’t prepare us how to cope.

I often get asked why I write such sad songs. For those who know me, I’m generally a happy-go-lucky person who likes a joke and a froyo more than just about anything in the world. My answer is two-fold: 1) I’m a deeply nostalgic person in ways very few people see; and moreso 2) melancholic feelings are just so much more interesting than pleasure and glee. Whereas we only have one major scale (okay, sure, this is debatable, leave me alone, music theory nerds), we need at least three to navigate minor keys, and this feels analogous to the depths and varieties of feelings melancholy can bring. There’s so much texture to depression, anger, and angst whereas joy seems somehow uniform to me.

It’s not hard to see how I got from the poem to the lyric – they share many concepts, words, and phrases in common. I remember that I wrote this tune in Montreux, Switzerland, shortly after the solo jazz piano competition there. I walked around that city, taking in its beauty, yet at the same time a bit lonely and lost (the competition had been the focus of so many aspirations and preparations, after all), and started mentally piecing together the lyric. I believe that this was the first song I wrote with this group (Lucas, Nancy, and myself) specifically in mind.

A couple musical details – this is an odd song in that it starts and ends in two different keys. It’s not something I set out to do, but I think I could make the argument that ending in D minor instead of A minor, the listener does feel slightly “lost”…in a new key never to return. This also helped to decide on the form of the tune, which includes three statements of the melody rather than any solos. Since the tune really “starts over” after each repetition, it seemed unnecessary and odd to try to create improvisations that might span two, three, or four repetitions. Each statement is self-contained, and hopefully the texture of loss develops and spreads from one statement to the next.

Download the chart for “One Art” for free here.

Download a free EP of music from the video series here.

One Art

I’d like to learn how to lose

By losing something new every day.

I’ll start with my keys and proceed to my shoes,

and soon it will all slip away.

I’ll reject my fortune

and regret my fame

Without choosing who

I’ll forget my friends’ names and faces.

I was so good at losing you

You left me without one final word.

But nothing I’ve tried has helped to erase

the memory of that last look on your face:

You smiled through tears in the winter’s frost

perhaps you knew that without you I’m lost.

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.